Updated August 2020

HeLa Cells

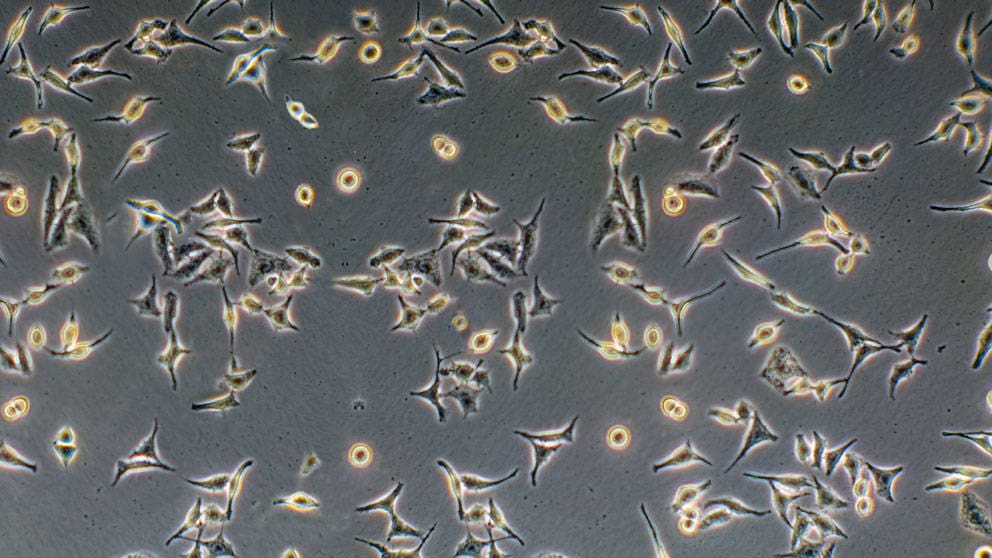

HeLa cells are human cells that became the first and most commonly used human cell line. They are cells that are live and reproduce in a test tube. HeLa cells have generated breakthroughs in cell biology, drug discovery, and the understanding of human disease.

I was an undergraduate research assistant when I first saw HeLa cells. When I saw the tube marked “HeLa,” the enormity and human aspect of the cells sunk in. The cells in this tube were from a woman, another human being. A woman treated unfairly, to put it mildly.

Holding the tube with her cells, I stood in awe of how the cell line became so universal. How a woman of just over five feet in stature had produced a cell line estimated to weigh 50 million metric tons – a mindboggling amount of cells given that a cell weighs next to nothing. These cells are in just about every biological laboratory in the world. Scientists today jest that HeLa is the most reproductively successful organism because the number of HeLa cells have far surpassed any other organism in the world and have become, in a sense, immortal.

But where did these cells come from? Whose DNA is responsible for some of the greatest advances in scientific history? For years, people did not know from whom HeLa cells were taken. Eventually, after many incorrect assumptions regarding the name of the woman, it was discovered that her name was Henrietta Lacks; hence, HeLa. More importantly, author Rebecca Skloot unveils the family’s story in her book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, from which much of the information here is derived.

The Woman Behind the Famous HeLa Cells

Henrietta Lacks was born August 1, 1920 in Roanoke, Virginia and given the name Loretta Pleasant, which she later changed. A few years after her birth, her mother, Eliza Lacks Pleasant, died during the delivery of one of Henrietta’s siblings. Henrietta’s father, Johnny Pleasant, wasn’t able to care for his 10 children, so they were split up among the family in Clover, Virginia. There, the family farmed tobacco fields that their ancestors worked as slaves.

Henrietta went to live with her grandfather, Tommy Lacks, in a log cabin. This small cabin was the former slave quarters of the plantation. It was here that she lived with her cousin David (Day) Lacks, who later became her husband. As children, the two would wake early to feed the animals, tend the garden, and toil in the tobacco fields. Henrietta walked two miles to the designated black school until sixth grade when she had to drop out to support the family.

Before marrying, Day and 14-year-old Henrietta had their first of five children, Lawrence, followed by Elsie (Lucile Elsie), David Jr. (Sonny), Deborah, and Joseph (Zakariyya). Elsie had epilepsy, although the term was not widely used at the time. Once Henrietta was pregnant with Joseph, she could not take care of Elsie. Doctors said it was best to send Elsie to Crownsville State Hospital (formerly the Hospital for the Negro Insane). Henrietta’s cousins say a part of Henrietta died that day. She would visit Elsie every week and was the last person to visit her before Elsie’s death at age 15.

Henrietta’s Knot

The Henrietta Lacks HeLa story starts with a visit to Johns Hopkins. This was the only hospital in the area that would serve black and poor people. Henrietta had previously felt a “knot” inside her, which doctors diagnosed as cervical cancer. She, like many other black women, could not afford to pay hospital bills. Doctors often took advantage of poor people’s situation by using them for research. In the doctor’s eyes, it was compensation for not paying. This research was conducted without informed consent; however, in 1951 there were no laws pertaining to consent or ethical violations. Laws were later established in part because of Henrietta’s story.

Henrietta’s doctor cut a piece of her tumor and delivered it to Dr. George Otto Gay, the head researcher at Johns Hopkins for cell growth. Dr. Gay was attempting to grow immortal cells. His goal was to create an environment to allow human cells to survive indefinitely in culture. Until Henrietta’s cells were available, researchers had not successfully grown human cells outside of the body.

It was the uniqueness of Henrietta Lacks’ cells that allowed scientists to discover which methods of cell culture worked. Her cells were hardy. Instead of dying in unfavorable conditions, the cells proliferated slowly, giving scientists the opportunity to identify the most favorable methods. They then applied these findings to other cell lines, thus determining how to most effectively culture cells. Without this now seemingly basic method, we would not have made many critical discoveries in biology. Countless routine medical tests and basic research would not be possible without culturing cells.

HeLa cells have had major roles in treatments, cures, vaccinations, and procedures. Rebecca Skloot captures this best: “There is not a person out there that has not benefitted from HeLa cells.”

The Short Version of a Long List of Scientific Advancements Impacted by HeLa Cells

- Development of treatments for Parkinson’s disease, AIDS, influenza, leukemia, hemophilia, and some cancers

- Formation of clinical trials for treating/curing cancers

- Discovery of a vaccine for polio

- Establishment of the field of virology, the study of viruses, such as Salmonella

- Development of methods for freezing cells for storage and standard cell culture

- Identification of the correct number of human chromosomes, leading to diagnosing genetic diseases

- Study of effects from radiation, deep sea pressure, and pharmaceuticals

- Research for space travel

- Discovery of the enzyme telomerase that has a role in cell aging and death

Why Henrietta’s Cells?

What was so special about these cancer cells that lead to the first immortal line? The answer is still unclear. Factors that likely played a role were the aggressiveness of her cancer, her cancer cells having multiple copies of the HPV genome, and Henrietta having syphilis, which suppressed her immune system and allowed for greater proliferation.

After being diagnosed with cancer, Henrietta started radiation to kill the cancer cells, which also killed many healthy cells. Several weeks into her treatment, she discovered she was infertile. Her doctors didn’t tell her that radiation would result in infertility. Her medical record reads, “Told she could not have any more children. Says if she had been told so before, she would not have gone through with treatment.” The radiation ultimately failed, and the cancer metastasized throughout her body. Henrietta died at age 31 on October 4, 1951, just eight months after she first felt that “knot.”

Fast forward to the 1970s when scientists, in an effort to learn more about Henrietta’s genetics, located her children to draw blood samples. Doctors called Day, Henrietta’s widower, to ask permission. Day was distrustful of white doctors and reluctant, an understandable response in light of the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment. Doctors failed to convey that the blood was for research. The family thought they were being tested for disease and awaited results that never arrived. At one point, Day was terrified when he thought Henrietta was still alive after hearing that her cells were reproducing in a laboratory.

It certainly would have been advantageous if a genetic counselor could have been present to help facilitate communication between the Lacks family and the doctors; however, the field was in its infancy.

Henrietta’s Legacy

Less than a year after I first held a tube of HeLa cells, I interviewed two descendants of Henrietta Lacks – Kimberly Lacks and Veronica Spencer, the granddaughter and great-granddaughter, respectively. It was surreal to talk to them about the ongoing effect their relative has had on our world.

“People from all over the United States come up to me with tears in their eyes, thanking me because they have a child because of the in vitro fertilization medication they took that was because of my grandmother’s cells,” Kimberly said. “Or that their child’s cancer is in remission because of the medication their child took that my grandmother’s cells helped create.”

Veronica highlighted a take-home message from her great-grandmother’s story – how essential self-assessment is in early detection of cancer.

Although Dr. Gay did not personally make monetary gains from HeLa cells, others have. Many argue the Lacks family hasn’t been appropriately compensated for the tremendous advances in science made possible by HeLa cells. In 2013, the NIH added two family members to a six-member committee that regulates access to the genome. The NIH also promised to acknowledge the family in research papers.

Last summer, HBO brought Rebecca Skloot’s book to the big screen. The film starred Rose Byrne as Skloot and Oprah Winfrey as Deborah Lacks (Henrietta’s daughter). Skloot worked closely with Deborah to uncover the story of Henrietta. Deborah, who died in 2009, was committed to learning about her mother’s life and sharing this experience with the world. Skloot said Deborah always wanted Orpah to play her and for the whole family to be involved with Henrietta’s story, both of which came true. Henrietta’s story will continue to be told and people will remember – HeLa cells are from a woman named Henrietta Lacks.

Written by Kira Dineen. This lightly updated story was originally published on August 1, 2016.